Articles

|

|

Whitehead puts all of us consumers to shame by being involved in every aspect of the Herculean task of production. Not only does he raise the silkworms, but he also reels cocoons into thread which he then weaves into silk, and dyes with natural indigo dye that he himself grows. There are no Japanese who carry out the whole process of raising, dying and weaving their own silk.

|

|

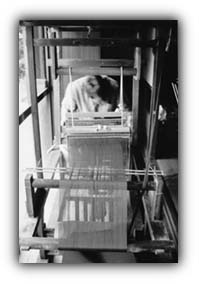

A 600-tsubo (1,980-sq.-meter) field of mulberry is just enough to make a few kilograms of silk. Thirteen thousand worms eat around 400 kg of leaf before they spin cocoons, of which only the best are selected for weaving. They are then boiled in water and unraveled (one cocoon yields a strand of 1,800 meters) and spun into thread of about 80 strands. Thirteen hundred of these "warped" threads are then hand-threaded into a traditional wooden loom. The weaving itself takes weeks and weeks of labor.

|

|

If you can imagine how fabric was made hundreds of years ago by women sitting at their looms, working the pedals of the machinery, then you get some idea of the process craftspeople such as Whitehead undertake to produce that raw silk we see in its final stage. So how then do you put a price on a kimono made from such material? A hand-painted kimono, or one that's dyed by indigo that takes one year to grow? "You don't," says Whitehead. "I'm not selling it!" Now, with the mountain cocoons that he has raised, the light-green raw silk that is spun by the similarly colored worms can sell for up to ¥40,000 per kilo. Needless to say, the market is almost non existent. The compromise for Whitehead is to involve the community in different aspects of the silk production and focus his own time on finding ways to crossbreed different types of silk moths and produce silk of a higher quality. Currently, he is crossbreeding Edo-period worms he has named the "blueflute" variety, to create a silk that is lighter and stronger. "I've been told that if I want to be a master craftsman I have to choose one aspect of the silk production to focus on. I was told that I'm going in too many directions," he says. "And they have a point, but I'm not going to stop, I want to master every aspect." By the end of the day, exhausted, everyone is spread out in chairs and on the floor in all corners of Whitehead's home. The older women of the community are in the kitchen watching over the boiling vegetables, while the men are outside, fanning the smoke from the miso-stuffed river trout they are grilling. Over the Sunday sounds of Billie Holiday and the rainlike munching of the silkworms, the open house feels more like a community center. Says Whitehead, "What's the purpose of being in Japan if you're not going to learn something Japanese?"

|