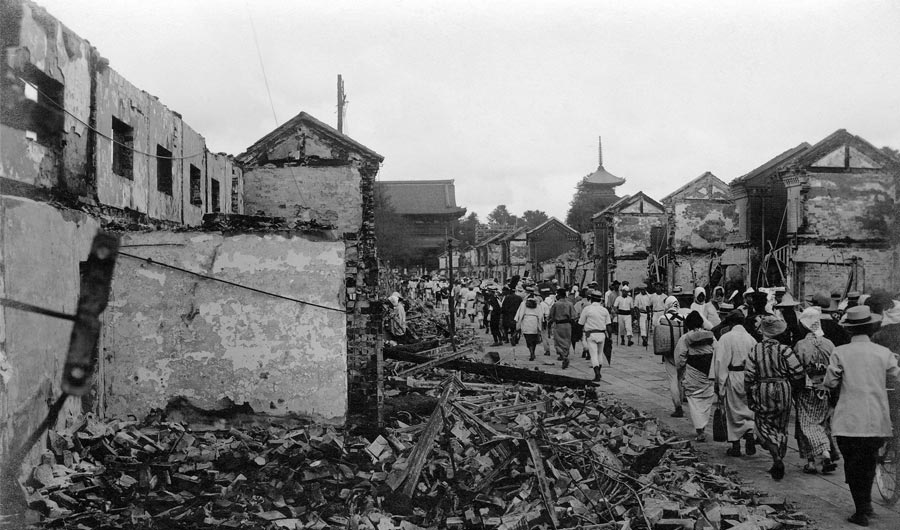

THE large photo of a crowd walking past shops along the approach to the Buddhist temple Sensoji was taken some time in 1934. Notice that while most men and even the children wear Western clothing, the women still wear kimono.

The shops, known as Asakusa Nakamise, were great crowd pleasers. Their origins are rooted in a harvest festival called Tori no Ichi. Held in November, long lines of people would wind their way along the rice pad- dies to pray and enjoy themselves at Sensoji. Naturally, this attracted a large number of merchants and entertainers, who were mostly located in the entertainment district behind the temple. Eventually, neighborhood merchants were allowed to open their shops in the approach to the temple as well.

Many of the shops developed “Asakusa Meibutsu,” or Asakusa specialties. These included Asakusa Nori (sheets of edible seaweed), Asakusa-gami (a kind of paper), Tondari Hanetari (small toys that jumped) and Fusayoji, or fairly large tufted tooth- picks made from willow trees or shrubs and used to clean the teeth as an early version of the toothbrush.

Many shops employed beautiful women to attract customers. Some of these kanban musume (literally “billboard girls”) became quite celebrated. Famous woodblock artists like Suzuki Harunobu (ca. 1724-1770) and Kitagawa Utamaro (ca. 1753-1806) created ukiyo-e woodblock prints of them. Especially

famous was O-Fuji, a kanban musume of the fusayoji shop Yanagiya. She was one of the three famous bijin (beautiful women) of the Meiwa Era (ca. 1764-1772).

English traveler and writer Isabella Bird (1831-1904) visited this area in 1878 and wrote this lively description of the atmosphere on the temple grounds:

“All over the grounds booths with the usual charcoal fire, copper boiler, iron kettle of curious workmanship, tiny cups, fragrant aroma of tea, and winsome, graceful girls, invite you to drink and rest, and more solid but less inviting refreshments are also to be had. Rows of pretty paper lanterns decorate all the stalls.”

“Then there are photograph galleries, mimic tea-gardens, tableaux in which a large number of groups of life-size figures with appropriate scenery are put into motion by a creaking wheel of great size, matted lounges for rest, stands with saucers of rice, beans and peas for offerings to the gods, the pigeons, and the two

sacred horses, Albino ponies, with pink eyes and noses, revoltingly greedy creatures, eating all day long and still craving for more.”

“There are booths for singing and dancing, 1 — crowd walks past the Nakamise shops along the approach to Sensoji, a Buddhist temple in Tokyo’s Asakusa

district, ca. May 1934. 2 — Nakamise today. 1 2 3 3 Asakusa Souvenir Shops and under one a professional story-teller was reciting to a densely packed crowd one of the old, popular stories of crime. There are booths where for a few rin you may have the pleasure of feeding some very ugly and greedy apes, or of watching mangy monkeys which have been taught to prostrate themselves Japanese fashion.”

In 1885, just seven years after Bird penned these impressions, brick shops were built for Asakusa’s first modern Nakamise. Merchants were selected by lottery and all other shops were removed from the temple grounds.

Shortly after, in March of 1889, American scholar Alice Mabel Bacon (1858–1918), the first Western woman to live in a Japanese household, visited these shops and delightfully described them in her book A Japanese Interior:

“When we had come as near to the temple as the kurumas (rickshaws) were allowed to approach, we got out to walk the rest of the way; but we had to pass a line of small shops, in which every conceivable variety of toy is kept, and so attractive was the display that we succumbed to the temptation, spent all our time at the toy-shops, and did not reach the temple at all.

I have made up my mind that if I undertake a collection of any kind while I am out here, it will be of toys. I think that in a complete collection of the toy tools, implements, furnishings, etc., one could bring home the largest possible amount of the every-day life of Japan, and with the least possible expenditure of money. I have begun with a ceremonial tea service, a box of carpenter’s tools, and a small kitchen. This last is the most perfect little thing that you can imagine, — a Japanese kitchen, with all its fittings and utensils, even to the knives and skimmers, the dust-pan, the matches, and the god-shelf. It is now before my eyes as

I write, and you might suppose you were looking into a kitchen through the wrong end of an opera-glass, for there are no shams about it; everything is made as carefully as if for use.”

The shops were destroyed during the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 and rebuilt in concrete in 1925. These were in turn destroyed during the aerial bombing of Tokyo in 1945 and rebuilt after the end of the war. The shops are still there today. They still attract huge crowds. But these days, there are more foreign tourists than Japanese. tj

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

The complete article is available in Issue #272. Click here to order from Amazon